|

|

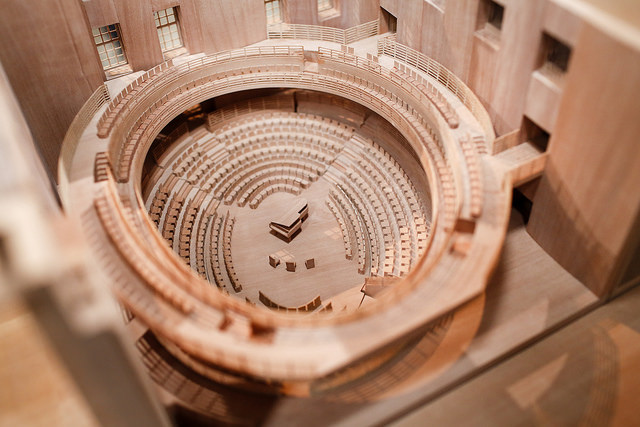

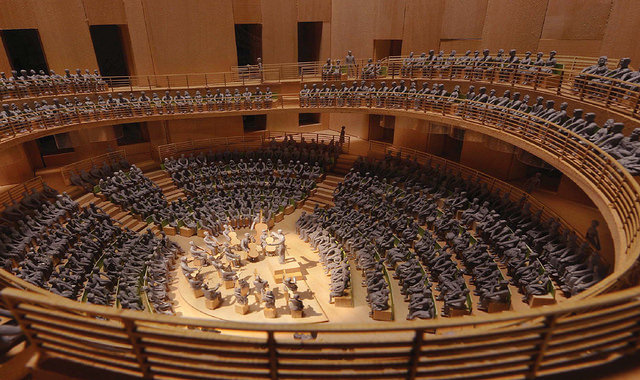

Berlin’s Pierre Boulez Saal has just opened to visitors. It won't be used for concerts for another nine months, but the models of the interior look pretty nice...

0 comments

Morton Feldman Beckett Material WER 73252

Morton Feldman is not a composer for those in a hurry. His works, especially towards the end of his life, unfold at a glacial pace with much repetition and extensive use of silence. And yet, if you are in the right frame of mind, they can be transporting. I discovered this in 2014 when I experienced a mesmerising performance of his 70-minute For Bunita Marcus at >reinhören in Basel. Morton Feldman is not a composer for those in a hurry. His works, especially towards the end of his life, unfold at a glacial pace with much repetition and extensive use of silence. And yet, if you are in the right frame of mind, they can be transporting. I discovered this in 2014 when I experienced a mesmerising performance of his 70-minute For Bunita Marcus at >reinhören in Basel.

The three works on this new disk from WERGO were written from April to July 1976 and grew out of a commission for the opera Neither based on a text by Samuel Beckett. They were meant to be preparatory sketches, though in the end none of the material found its way into the opera. Whilst not composed on the scale of Bunita – they are 17, 19 an 8 minutes each – they do share the a similar spareness of texture. This is apparent in Orchestra, which consists of a gesture here, an idea there, a period of silence then a sudden outburst. Elemental Procedures has a much greater emphasis on melodic writing and accompaniment, with the inclusion of a soprano soloist and choir. The result is a little more sumptuous, but only a little. Routine Investigations is more pared down still, being for only six instruments. Though it’s brittle argument takes place over a much shorter span, the pace of development remains slow.

If you are unfamiliar with Feldman I would hesitate to recommend this disk as a starting point. Even though it is longer, the densely interwoven textures of his final orchestra work, Coptic Light (1986), are more immediately compelling. For those with a little more familiarity, they make a good stepping-stone to his most epic pieces such as For Philip Guston and String Quartet II (each lasting over three hours). As in all Feldman you will need to be in the zone to appreciate the slow rate of change. They are like the test cricket of classical music – the action is spaced-out, apparently inconsequential. To the newcomer it is baffling; to those in the know, compelling.

Marina Khorkova klangNarbe WER 64182

Even though I haven’t been able to get hold of a copy yet, I also urge you to seek out a debut double-disk set by Russian composer Marina Khorkova, also on WERGO. I had the pleasure of meeting Marina in Switzerland a couple of years ago. She sat me down with an excellent pair of headphones and picked out a few of her pieces to listen to. I was immensely impressed by what I heard, especially her ability to think of ways of eliciting new sounds from traditional instruments. Good examples of this are her Installationen I and Installationen II for organ (2012), still available at her Soundcloud page. For these pieces she spent weeks working on one instrument, experimenting with unusual combinations and settings (for example using stops pulled out by 1/3, 2,3 or full). The results, especially in Installationen II, are compelling. You can learn more about Marina’s work in an interview she did for CT shortly after our meeting. Even though I haven’t been able to get hold of a copy yet, I also urge you to seek out a debut double-disk set by Russian composer Marina Khorkova, also on WERGO. I had the pleasure of meeting Marina in Switzerland a couple of years ago. She sat me down with an excellent pair of headphones and picked out a few of her pieces to listen to. I was immensely impressed by what I heard, especially her ability to think of ways of eliciting new sounds from traditional instruments. Good examples of this are her Installationen I and Installationen II for organ (2012), still available at her Soundcloud page. For these pieces she spent weeks working on one instrument, experimenting with unusual combinations and settings (for example using stops pulled out by 1/3, 2,3 or full). The results, especially in Installationen II, are compelling. You can learn more about Marina’s work in an interview she did for CT shortly after our meeting.

Other recent releases

For fear of toadying, I refuse to review the disk Gumboots on Signum Classics by CT’s very own David Bruce. I will tentatively say, however, that I found it most enjoyable… Go and listen for yourself – it’s available for digital download and streaming on Spotify and Apple Music.

Aside from the Khorhova and Feldman there are three other new disks out on Wergo. Improvisation Ajountée contains works for organ by Maurice Kagel; there is a new recording of Pēteris Vasks’ String Quartets 1, 3 and 4 played by Spīķeru String Quartet; and first recordings of chamber works by Balz Truempy. NMC have just released Colin Matthews’ violin and cello concertos and a collection of chamber music by Mark Simpson. They are also continuing their Sinfonietta Shorts project with Francisco Coll’s Hyperlude IV and Matt Rogers’ Orac. On Divine Art there are two very different collections of song setting: one by Philip Wood, the other by Michael Finnissy. Both are available for streaming. There is also a collection of choral music by Lydia Kakabadse and a programme of Miniaturised Concertos by a selection of contemporary composers. On Naxos, finally, are recordings of choral music by John Rutter, Randall Thompson’s Requiem, Xia Guan’s Symphony No. 2 and a selection of orchestral music by a man better known for his writing, Anthony Burgess.

View playlists of this month’s releases

To see a selection of this months new releases, take a look at my playlists at Apple Music or Spotify (whichever you prefer). The Spotify playlist is collaborative, in case you'd like to add to it.

0 comments

The New York Times described the inaugural NY Philharmonic Biennial as ‘Perhaps the most ambitious and extensive contemporary-music festival yet overseen by an American orchestra.’ The 27 events in the second edition (23rd May–11th June) encompass a festival within a festival–the New York City Electroacoustic Festival, a series of programmes that centre around the music of Ligeti, a number of regional and world premieres (though a new work from Esa-Pekka Salonen, originally scheduled for the last night, appears to have been dropped) and concerts dedicated to young and emerging composers. I would also highlight the first U.S. staging of Gerald Barry’s The Importance of Being Earnest, a superb work that won many plaudits during its first run and recent revival in the UK.

The centrepiece of the 2016 Aldeburgh Festival (10th–26th, Aldeburgh, UK) is a journey through Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux, his 13-movement work for piano based on birdsong. On 17th there are twelve events dedicated to it, including outdoor performances at sunrise and sunset, talks and films. Many have already sold out, though the organisers are promising that more tickets will be available soon. Even if not, it’s still worth pitching up–there will be a free audio relay of the concerts and several events don’t require tickets. Other things to look forward to include works by the festival’s three featured composers, Julian Anderson, Benedict Mason and Rebecca Saunders, as well as new pieces inspired by the First World War. The music of the festival’s founder, Benjamin Britten, will this year be juxtaposed with that of his contemporary Michael Tippett.

It may be the first St. Magnus Festival (16–26th, Orkney, UK) without Max, but there is still a world premiere to look forward to. On 20th there will be the first performance of his Wendy’s Wedding Music at Sanday Community School, written to celebrate the marriage of its headteacher. The music of the festival founder can also be heard in seven other concerts, all viewable here. There are also new works from John Gourlay, Jennifer Martin, Sheena Phillips, Andra Patterson and Mogens Christensen as well as 10 short premieres for solo cello on 25th. Elsewhere there is plenty of music by living composers and, don’t forget, the festival offers a wide range of other categories for the culturally-minded, including literature and theatre; folk, jazz and world music; films; and community events.

The Holland Festival (4th–26th, Amsterdam) has a similar spread of cultural events and also a good deal of new music. Perhaps the highlight is The Transmigration of Morton F. on 20th. Devised by director Sjaron Minailo and composer Anat Spiegel, it promises to be a surreal blend of opera, ritual and computer-gaming. On 23rd the Kronos Quartet give the world premieres of Yannis Kyriakides’ The Lost Border Dances and a new work by Merlijn Twaalfhoven. There are also a number of Dutch premieres, including Birtwistle’s The Cure and The Corridor on 9th and 10th, as well as the chance to see one of the twentieth century’s greatest operas Wozzeck on the opening day.

Other forthcoming premieres…

Another Maxwell Davies world premiere, his children’s opera The Hogboon, takes place at the Barbican under Sir Simon Rattle on 26th June. Also in London, on the 1st the London Sinfonietta present new works from Tom Coult and Harrison Birtwistle together with a pair of regional premieres, whilst on 19th the chamber ensembles from the LSO will, as part of their Soundhub scheme, present new works from next generation composers Yasmeen Ahmed, Ben Gaunt, Oliver Leith and Lee Westwood. At Hoddinott Hall in Cardiff, finally, BBCNOW give the world premiere of John Pickard’s Symphony No. 5 on 7th.

0 comments

Palmyra Concert

Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky Opera Orchestra gave a concert at Palmyra yesterday. The recapture of the ancients ruins by Russian-backed troops was one of the few pieces of good news to come out of Syria recently. Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky Opera Orchestra gave a concert at Palmyra yesterday. The recapture of the ancients ruins by Russian-backed troops was one of the few pieces of good news to come out of Syria recently.

As I’ve written elsewhere, music has always been a target of Daesh (also known as IS), so a concert at Palmyra could have been a wonderful opportunity for bridge-building and reconciliation. Sadly the musicians and most of the audience were Russian, the solo cellist was Sergei Roldugin, a close friend of Putin (and who, in the Panama Papers, was recently revealed to possess many millions in offshore holdings) and the Russian President himself appeared via video link from Moscow to hail the operation to liberate Palmyra. Even Gergiev, a conductor who would anyway do better to spread himself less thinly, is a vocal supporter of Putin. The concert therefore became nothing more than a PR exercise, with music as sadly mistreated by those who allow it as by those who would suppress it.

Apple Music Redesign

It has just been leaked that Apple Music will be getting a redesign, with full details being revealed at an Apple Keynote at WWDC on June 13th. I reviewed the new service in July 2015, comparing its catalogue and system for organising tracks favourably with Spotify. I still think that, for collectors, Apple Music, with its superior organisational tools, is a great option. The criticisms of its interface are, however, justified. The ridiculous search bar, where you are invited to look in either your own library or Apple music, is a constant frustration. Often I can’t find what I’m looking for because I’m inadvertently looking in the wrong place. Whenever I need something quickly I always fire up Spotify. It has just been leaked that Apple Music will be getting a redesign, with full details being revealed at an Apple Keynote at WWDC on June 13th. I reviewed the new service in July 2015, comparing its catalogue and system for organising tracks favourably with Spotify. I still think that, for collectors, Apple Music, with its superior organisational tools, is a great option. The criticisms of its interface are, however, justified. The ridiculous search bar, where you are invited to look in either your own library or Apple music, is a constant frustration. Often I can’t find what I’m looking for because I’m inadvertently looking in the wrong place. Whenever I need something quickly I always fire up Spotify.

At least on mobile devices things work relatively smoothly. In iTunes on a computer the experience is much less peachy. There are recent horror stories of it deleting users’ music libraries (though read this rebuttal) and the program certainly does too much: it hosts the iTunes store, device syncronisation, videos, podcasts, audio books, users’ music libraries and Apple Music. It is a bewildering experience, even once you are used to it. Unsurprisingly, given its baroque complexity, neither does it work very reliably. Often I click on a track or search for something obvious and nothing happens. It’s time Apple did what it does on iOS – divide iTunes so that each part has its own app: videos, podcasts, iTunes Store, Apple Music.

This is a Voice (Wellcome Collection, London, 14th April–31st July)

I missed this fantastic-looking exhibition when doing my events roundups in March and April but, thankfully, there’s still plenty of time to pay a visit. As the name of the show suggests, the exhibition examines the human voice in a kind of ‘acoustic journey’ with ‘works by artists and vocalists, punctuated by paintings, manuscripts, medical illustrations and ethnographic objects.’ To get a more detailed flavour of the exhibits you can peruse the Gallery Guide. I missed this fantastic-looking exhibition when doing my events roundups in March and April but, thankfully, there’s still plenty of time to pay a visit. As the name of the show suggests, the exhibition examines the human voice in a kind of ‘acoustic journey’ with ‘works by artists and vocalists, punctuated by paintings, manuscripts, medical illustrations and ethnographic objects.’ To get a more detailed flavour of the exhibits you can peruse the Gallery Guide.

One of the most intriguing exhibits, Matthew Herbert’s ‘Chorus’, was featured on BBC Radio 3’s In Tune (see the podcast from 14th April). It is a recording booth in which visitors are invited to sing a single note, which is then added to an ever-growing chorus. The effect is compelling and not a little unnerving, rather in the manner of Ligetian micropolyphony. There is also an online version which, if you can’t make the exhibition, I thoroughly recommend. It allows you to isolate voices by the week in which they were recorded and by seemingly random options such as ‘outside temperature’ and ‘local traffic disruptions when the voices were recorded.’ It’s a lot of fun.

And on BBC iPlayer…

If, like me, you missed the BBCSO Dutilleux Total Immersion Day you can catch up with the final concert on BBC iPlayer. It features a good cross-section of his output: his transitional Symphony No.1; Métaboles, which marked the emergence of the composer’s mature style; the sublime cello concerto Tout un monde lointain…, originally written for Rostropovich; and Dutilleux’s moving response to the the suffering of the Jews during the War, The Shadows of Time. The recording is available until the end of this month.

0 comments

York Spring Festival (4th–8th)

.png) The seven concerts form part of the YorkConcerts series. There is a good array of new music on offer, from works written by students to more established composers. The highlight, perhaps, is a concert celebrating the 70th birthday of Michael Finnissy on 7th. In it pianist Ian Pace will play works by Percy Grainger, Steve Crowther, Beethoven and Lawrence Crane. There will also be new works by Andrew Toovey, Luke Stoneham and Finnissy himself. There is a pre-concert talk with the composer at 6.45. The seven concerts form part of the YorkConcerts series. There is a good array of new music on offer, from works written by students to more established composers. The highlight, perhaps, is a concert celebrating the 70th birthday of Michael Finnissy on 7th. In it pianist Ian Pace will play works by Percy Grainger, Steve Crowther, Beethoven and Lawrence Crane. There will also be new works by Andrew Toovey, Luke Stoneham and Finnissy himself. There is a pre-concert talk with the composer at 6.45.

Vale of Glamorgan Festival (10th–20th)

The festival concentrates entirely on the music of living composers. This year there is a special emphasis on the music of John Metcalf and Pēteris Vasks, both 70 this year, and Steve Reich, who is 80 in October. There will be three chamber works by Metcalf on 18th and Vasks’ substantial Piano Quartet; the BBC National Orchestra of Wales concert on 20th will feature the world premiere of Vasks’ Viola Concerto; and three concerts, on 11th, 14th and 18th, will feature the music of Reich. Other composers represented include Parmela Attariwala, Ēriks Ešenvalds, Magnus Lindberg, Per Nørgård, Arvo Pärt, Krzysztof Penderecki, Guto Puw, Bent Sørensen, Andrew Staniland, Hilary Tann and John Tavener. The complete list, together with links to the concert in which their works feature can be viewed here.

Prague Spring Music Festival (12th–June 3rd)

.png) The events actually start on 7th with a concert from the winner of the Chopin Piano Competition 2015 and competitions for trumpet and piano soloists. The main festival gets going on 12th. Very recently written music is a little thin on the ground, but there are twentieth century works from the likes of Bernstein, Stravinsky, Berg, Lutosławski and Gorecki. There is also the chance to hear the Czech premiere of Colin Matthews’ Traces Remain on 26th and Pēteris Vasks’ Little Summer Music on 1st June. The events actually start on 7th with a concert from the winner of the Chopin Piano Competition 2015 and competitions for trumpet and piano soloists. The main festival gets going on 12th. Very recently written music is a little thin on the ground, but there are twentieth century works from the likes of Bernstein, Stravinsky, Berg, Lutosławski and Gorecki. There is also the chance to hear the Czech premiere of Colin Matthews’ Traces Remain on 26th and Pēteris Vasks’ Little Summer Music on 1st June.

Norfolk & Norwich Festival (13th–29th)

.jpg) This festival includes theatre, art and literature as well as music. All of the classical events are listed here. Two events worth making a special trip for are the world premiere of Cain, a new choral work by Kemal Yusuf; and a concert dedicated to the music of Max Richter, consisting of his The Blue Notebooks and selections from Sleep (the original of which is designed to be sleep through over 8 hours – an experience I tried, with somewhat disturbing results). This festival includes theatre, art and literature as well as music. All of the classical events are listed here. Two events worth making a special trip for are the world premiere of Cain, a new choral work by Kemal Yusuf; and a concert dedicated to the music of Max Richter, consisting of his The Blue Notebooks and selections from Sleep (the original of which is designed to be sleep through over 8 hours – an experience I tried, with somewhat disturbing results).

English Music Festival (26th–30th)

The festival focuses entirely on English music from the Renaissance to the present day. There are two premieres of works that are newly discovered or have otherwise been overlooked: Percy Sherwood’s Concerto for Violin and Cello and Vaughan Williams’ Fat Knight. Works by living composers include Paul Lewis’s An Optimistic Overture; David Matthew’s Norfolk March; Daniel Gillingwater’s Overture, Ad Fontem; and Paul Carr’s Violin Concerto. The festival focuses entirely on English music from the Renaissance to the present day. There are two premieres of works that are newly discovered or have otherwise been overlooked: Percy Sherwood’s Concerto for Violin and Cello and Vaughan Williams’ Fat Knight. Works by living composers include Paul Lewis’s An Optimistic Overture; David Matthew’s Norfolk March; Daniel Gillingwater’s Overture, Ad Fontem; and Paul Carr’s Violin Concerto.

0 comments

Christian Morris talks to Jack Sheen, composer, conductor and co-founder of the ddmmyy concert series.

|

|

Jack Sheen |

How did you come to found the ddmmyy series?

I wasn't actually involved in the first ddmmyy show, 090212. That was ran by Tom Rose and Laurie Tompkins - who now direct the Slip imprint together - when I was in my first year at music college in Manchester. They were in second and third year respectively. I came onboard for the second gig, 250512, to conduct and gradually became more involved along with other composers. It's now just myself and Tom.

Those early days of ddmmyy back in 2012 really set the tone for how the series continues to operate. It's still a bunch of mates writing music, talking about music together, introducing each other to music, and then somehow amalgamating all of this into a bespoke event. It's still about presenting new music alongside pieces that we love and feel contextualise each other nicely, except this 'group of mates' has vastly expanded since 2012.

I know that sounds quite corny but it's really how I feel about it all! I've never worked with anyone in ddmmyy that I haven't gotten along with and felt like I've struck up a personal relationship with in the process of commissioning or performing their music. A love of people and the music they make. I just hope that can continue really.

>>Click here to read the rest of the interview

0 comments

The music of Czech composer Martin Smolka was unfamiliar to me until I came across this new disk of his choral works on Wergo. The programme contains his Poema De Balcones; Walden, The Distiller of Celestial Dews and Słone i smutne. The works are written for large choral forces, the clustered textures occasionally recalling the avant-garde techniques of the 60s. What sets these pieces – the first two in particular – apart, however, is that, though clearly aware of their antecedents, they wear this knowledge lightly. The music of Czech composer Martin Smolka was unfamiliar to me until I came across this new disk of his choral works on Wergo. The programme contains his Poema De Balcones; Walden, The Distiller of Celestial Dews and Słone i smutne. The works are written for large choral forces, the clustered textures occasionally recalling the avant-garde techniques of the 60s. What sets these pieces – the first two in particular – apart, however, is that, though clearly aware of their antecedents, they wear this knowledge lightly.

Poema De Balcones takes a few elliptical lines by Frederico Garcia Lorca (el mar baila por la playa/ un poema de balcones/ retumba el agua), reimagining them in sound. Though the text becomes lost, the composer treating it very freely, its essence is translated into a brilliantly persuasive sound picture. There is naivety in its pictorial directness, though this is also part of its charm–clustered crescendoing chords seem to depict the languid sea, the whistling of the choir the birds overhead. The style is harmonically rich, though at all times chords are chosen to preserve a sense of consonance. The gradual pace of change suggests a work designed to be wallowed in, but there is also a clear sense of direction: the overlapping crescendoing chords become more instant before leading to a central stasis finally followed by both a continuation and development of the opening ideas. The effect is magical.

Each of the five movements of Walden, the Distiller of Celestial Dews sets an excerpt from Thoreau's Walden; or Life in the Woods, a book that describes living simply in natural surroundings. Like the first work on the disk, the texts are treated quite freely, Smolka picking small sections of text to concentrate upon. Only in the anguished (and often detuned) homophony of the third movement Indians, is it set almost as it appears on the page. As in Poema De Balcones much of the writing is pictorial, most strikingly in the second movement Lake, where the the serene surface (‘smooth as glass’ sung repeatedly) is disturbed by little scraps of other material, almost as if a pebble were being thrown in the water. The harmony retains the kind of clustered consonance present in Poema (albeit a little stretched in the aforementioned third movement), though Smolka isn’t above a nice simple melody, such as the repeating unison ideas that begin the first and last movement. There is also a delicious hypnotic phrase in the fourth movement on the words ‘cinquefoil, blackberries’, which is alternated with a syncopated passage that suggests a fondness for jazz.

It’s not exactly more of the same in the last work on the disk, an eighteen-minute setting of Polish poet Tadeusz Różewicz’s Słone i smutne. The texts, once again, are treated very freely, and many of the stylistic fingerprints of the other works are here. They are, however, dialled up a little. The structure is improvisatory and, as such, harder to discern; the clustered harmony tends to emphasise the dissonant, melodic lines are more angular. That the composer took a more instinctive approach is revealed in his observation: ‘If you analyse it then you can find short melodic fragments, cluster-like sounds and many repetitions of short passages. I knew this was just what I had to write, I don’t know why.’ The result is certainly more challenging, but the quality and variety of the ideas keeps the listener engaged.

In his Manifesto of a Re-tuned Composer Smolka remarked ‘Please, no more musical revolutions. [...] Please, no more new music, but rather strange music.’ If I had to sum up Smolka’s style without being technical, I’d say he makes the strange accessible and the accessible strange. In my opinion this is the hardest compositional line of all to walk; to be challenging is not so difficult, playing to the gallery not so hard either. In this beguiling disk Smolka pulls off the rare trick of managing to do both.

Poema de Balcones is available on Spotify and Apple Music.

0 comments

2.jpg) Open Up Music. Image credit: Sarah Bentley. Open Up Music. Image credit: Sarah Bentley. |

There is something poignant about a world premiere of a composer who is no longer with us. Such is the case with the first performance of Peter Maxwell Davies’s Piano Sonata No. 2, which will be played by Rolf Hind at Wigmore Hall on 27th April. It is testament to Maxwell Davies’s strength that the flow of new works appears to have continued to the end – we also have his new children’s opera The Hogboon to look forward to on 26th June.

On 16th at Bristol Cathedral the University of West of England Singers, Lydbrook Band and members of the South-West Open Youth Orchestra conducted by Ian Holmes will give the first performance of a new version of Liz Lane’s Silver Rose. This is an especially important event since the work has been adapted to allow the participation of the disabled-led South-West Open Youth Orchestra. The instruments for this orchestra are adapted to the needs of individual musicians by the organisation Open Up Music. Not only does this allow much greater participation, but has the potential to open up new creative possibilities for composers. Lane, who is heavily involved in the creation of new repertoire for the orchestra told me recently that, as well as adapting standard instruments, the technical team is working on the development of a new musical instrument for the National Open Youth Orchestra planned for 2018/19. She admits it is ‘early days yet’, but has promised to keep us informed. In the meantime, do take the opportunity to hear the first steps in this excellent initiative.

Dutilleux’s 100th birthday celebrations continue this month with a BBCSO Total Immersion event at the Barbican on 30th April. It begins with an introduction to the composer by musicologist Caroline Potter, followed by a lesser-known work: a screening of the 1952 film L’amour d’une femme, for which Dutilleux provided the soundtrack. At 5pm Guildhall musicians concentrate on the composer’s chamber works, including his seminal string quartet Ainsi la nuit. Another talk by Caroline Potter follows at 6.30pm, acting as an introduction to a concert at 7.30pm with BBCSO consisting of Symphony No.1, Tout un monde lointain, The Shadows of Time and Métaboles.

The Budapest Spring Festival (8th–24th) has a number of events which will be of interest to lovers of new music. On 13th the Budapest Festival Orchestra will play John Adams’ Harmonielehre alongside works by Liszt and Bartók; on the same day there will be performances of new works by Steven Mackey and Uri Caine; the King’s Singers perform works by Morley, Reger, Ligeti, Bartók, Biebl, Kodály and Bob Chilcott on 19th; and on 22nd the will be the premiere of László Dubrovay’s ballet Faust, the Damned as well as Light from the Outside World by crossover DJ Jeff Mills. The Wittener Tage Für Neue Kammermusik (Witten Days for New Chamber Music), meanwhile, runs from 22nd–24th in Witten, Germany. There are a total of 20 world premieres and works first commissioned by Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR). The complete programme can be viewed here.

There are four opportunities to hear works by emerging composers. At IRCAM, Paris on 15th composers from the Cursus 1 programme (composition and computer music training) present their new works for solo instrument and electronics. On 24th there are two celebrations of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death: at Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, five composers will have works performed by the BBC Philharmonic; whilst at Peninsula Arts Plymouth University students will present their new songs alongside works by Clive Jenkins, Roxana Panufnik and Gerald Finzie. On 27th at Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, finally, the BBCNOW Composition: Wales – Open Workshop presents works by Welsh composers worthy of wider exposure.

Other world premieres to look forward to this month include: in the Tenri Cultural Institute, NYC on 2nd, Scott Wheeler’s Ben Gunn, presented alongside works by Virgil Thomson and Judith Weir; on 3rd in The Coronet Theatre, London a new work by George Lewis for solo guitar and ensemble; also on 3rd Nathan Theodoulou’s Jazz Concerto Grosso; and Franck Krawczyk’s Après receives its first performance by the NWP on 26th at the David Geffen Hall, NYC.

Regional premieres include the first US performances of Invisible Door for harpsichord and violin by Hyo-shin Na in San Francisco on 3rd; and Chaya Czernowin’s Hidden in Boston on 29th. In the UK, meanwhile, there are first performance of works by Hans Abrahamsen: Ten Studies at Wigmore Hall on 27th (in the same concert as the Maxwell Davies world premiere, above) and Concerto for the Left Hand at Birmingham Symphony Hall on 28th.

30th March

Some additional concerts, including two world premieres, that I missed in my original roundup. For additional information, see CT's concert listings:

Berg/Hesketh Die letzten Augenblicken der Lulu - A 'Lulu' Redaction *World Premiere* | 31 March 2016 | Sarah Gabriel, soprano, Françoise-Green Piano Duo | St John's Smith Square, London

Hände: Das Leben und die Liebe eines Zärtlichen Geschlechts - for piano with film | Clare Hammond, piano | 7 April 2016 | Woodend Barn, Aberdeen for Sound Festival, Scotland

Hände: Das Leben und die Liebe eines Zärtlichen Geschlechts - for piano with film *London Premiere* | Clare Hammond, piano | 9 April 2016 | Kings Place (Hall 2), London

In Ictu Oculi (Three Meditations) for Wind orchestra *World Premiere* | National Youth Wind Ensemble, Phillip Scott, conductor | Royal College of Music | 9 April 2016

0 comments

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies was one of a handful of composers truly to have dominated British cultural life, also winning a worldwide reputation with his substantial body of work. Sometimes called by his full name, sometimes Maxwell Davies or Sir Peter, he was just as often known affectionately by fellow musicians as Max. Sir Peter Maxwell Davies was one of a handful of composers truly to have dominated British cultural life, also winning a worldwide reputation with his substantial body of work. Sometimes called by his full name, sometimes Maxwell Davies or Sir Peter, he was just as often known affectionately by fellow musicians as Max.

His life can seem contradictory. He was the enfant terrible who wrote educational works for children; the ardent republican that liked the Queen; a pervasive cultural figure who lived in remote Orkney. In many respects one could say that he trod the typical artistic path—the outsider who was eventually absorbed into the establishment. It would be fair to say, however, that his assimilation did not dull his radical roots or his ability to stand up for what he thought was right. This was apparent when in 1993 the Arts Council proposed to remove funding from two London Orchestras. He threatened to renounce his knighthood and quit the country.

His ability to adapt his style to a compositional brief, writing educational works for children and other light pieces such as Farewell to Stromness (which made him one of the few contemporary composers represented in the Classic FM Hall of Fame), puts him in the tradition of community-rooted British composers such as Benjamin Britten or the present Master of the Queen’s Music, Judith Weir.

This image stands in apparent contrast with the radical composer that emerged in the 1960s, the heir-apparent to such figures as Ligeti, Lutosławski, Berio and Xenakis. During that time he wrote a number of technically challenging and provocatively political or anti-religious works that earned him the reputation as a being ‘difficult’. First Fantasia on an In Nomine of John Taverner (1962), for example, had to be conducted by the composer at the BBC Proms because Sir Malcom Sargent found it too demanding, whilst the first performances of Eight Songs for a Mad King and Worldes Bliss (both 1969) provoked catcalls and, in the case of the latter, an audience walk-out. His compositional range and ability to adapt a variety styles to his own ends was, in fact, always an intrinsic part of his musical personality.

Following his studies in Manchester, where he became associated with composers Harrison Birtwistle and Alexander Goehr, pianist John Ogden and trumpeter and conductor Elgar Howarth, Maxwell Davies became a teacher at Cirencester Grammar School in 1959, composing works such as O Magnum Mysterium and the Five Klee Pictures, for the pupils there. This interest in composing for amateurs remained with him for the rest of his life. It would manifest itself in works written specifically for children, such as the music-theatre works from 1989–91; in collaboration with them, as in the Strathclyde Concertos; or in his ability otherwise to moderate his style to accommodate an audience, as in An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise (1985).

This is not, of course, to undermine the significant and serious contribution Maxwell Davies made to almost every form of contemporary classical music. The foundation of his style was laid in the 50s and 60s. In his earliest acknowledged work, the Trumpet Sonata Op.1 (1955), he experimented with strict forms of serialism. Though his approach subsequently loosened, there always remained a strong tendency towards numerical compositional pre-planning, most obviously in his use of magic squares. At the same time strong modal/tonal elements endured, though the extent to which they operated in the foreground tended to be in proportion to the commission in hand. He used found material, especially from Renaissance composers, for example in his Alma redemptoris mater (1957), also adopting the techniques of the period to his own ends, as in Prolation (1958) where, he observed, they are ‘carried to manic extremes.’ Twentieth-century popular forms also appear, sometimes giving the impression of polystylism. Obvious examples being his use of foxtrots in St Thomas Wake (1969) and Missa Super L’Homme Armé (1971), in both cases allowing him simultaneously to tweak the nose of religion, a favourite target.

Davies’s first opera, Taverner (1962–8), took as it theme the life of the English Renaissance composer, also using his In Nomine theme as a compositional motive. This melody was to recur in many other works, including his chamber opera The Martyrdom of St. Magnus (1976). His other operas include The Doctor of Myddfai (1996), Resurrection (first begun 1963 but not finished until 1987) and The Lighthouse (1980). This last opera, a claustrophobic psychological drama based upon a true story, is probably also his best-known.

Davies’s move to Orkney in the 1970s coincided with a relaxation in his style. In a sign of his increased separation from the European avant garde it also led to a preoccupation with traditional symphonic music. The most substantial contributions were his 10 symphonies, the first in 1976, the last completed as he received treatment for leukaemia in 2014. There were also ten Strathclyde Concertos written for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, concertos for violin, piano, trumpet and horn and three concert overtures. Between 2002–7 he wrote 10 string quartets, commissioned by Klaus Heymann of Naxos Records.

In 1977 Maxwell Davies founded the St. Magnus Festival, remaining artistic director until 1986. As well as premiering many new works it remains heavily involved in outreach and educational work, most significantly in its composition course, now among the UK’s most important pilgrimages for ambitious composers.

Maxwell Davies received many honours during his lifetime. He was appointed a CBE in 1981, knighted in 1987 and was awarded the Companion of Honour in 2014. In 2004 he was also appointed, for a ten-year tenure, Master of the Queen’s Music. He received the Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal in February 2016.

Peter Maxwell Davies's Second Piano Sonata will be premiered on 27th April; his children’s opera, The Hogboon, on 26th June.

0 comments

In my teens I spent many a happy hour digging around in the Welsh Music Information Centre, a repository for scores and recordings of mostly recently written music from the principality. It proved a useful introduction to some of the most important names in Welsh music and in one case – the music of William Mathias – inspired a lifelong passion. In my teens I spent many a happy hour digging around in the Welsh Music Information Centre, a repository for scores and recordings of mostly recently written music from the principality. It proved a useful introduction to some of the most important names in Welsh music and in one case – the music of William Mathias – inspired a lifelong passion.

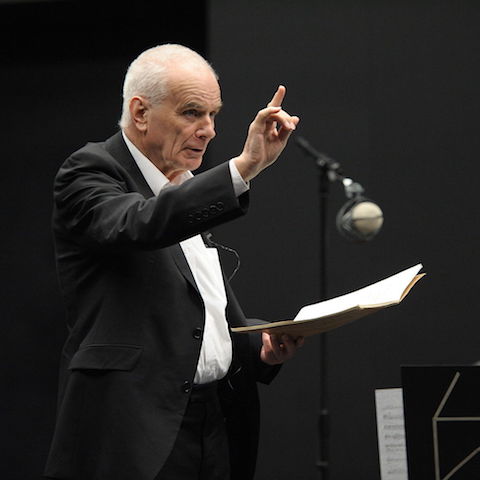

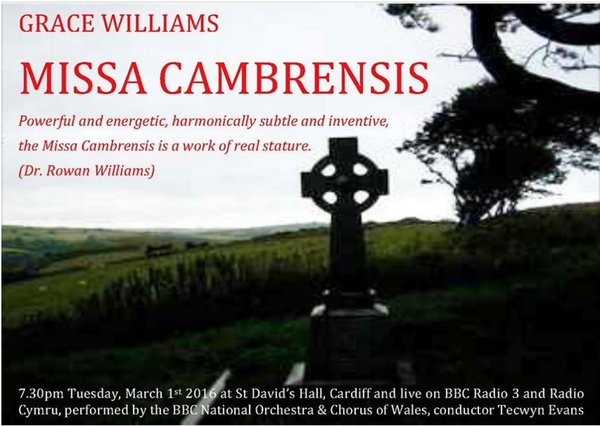

On one visit to the WMIC I remember its Director A.J. Heward Rees digging out a recording of the 1971 premiere of Grace Williams’ Missa Cambrensis. The performance was execrable. In fact, as he explained to me, the occasion was something of a cause célèbre in the life of the composer. The work had been greatly anticipated, the composer’s only opera The Parlour having been well-received a few years earlier. Unfortunately the massed choir and Llandaff Cathedral boys’ voices proved incapable of coping with Williams’ vocal writing. To add to these woes, two of the soloists withdrew before the concert.

Grace Williams was distraught after this debacle and never returned to the work. It has, since that day, often been viewed as a forgotten masterpiece, an unjustly neglected work. Down the years I have occasionally thought about it. Even though the recording that I had listened to at the WMIC had been disappointing, in the manner of all great music badly performed the work had a way of communicating through the shortcomings. It was difficult to understand why it had never been given a second chance. That chance, happily, arrived a little over a week ago in a St. David’s Day revival of the work in Cardiff with the BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales conducted by Tecwyn Evans.

The Missa is conventional in form, except in the Credo, which, in manner reminiscent of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, interpolates material from other sources, in this case Carol Nadolig by Saunders Lewis and The Beatitudes. The carol is performed by a boys’ choir, which also feature significantly in the Sanctus, The Beatitudes (in Welsh) by a narrator, in this case former Archbishop of Canterbury Dr. Rowan Williams. The lineup was completed by SATB soloists: Fflur Wyn, Catherine Wyn Rogers, Andrew Rees and Jason Howard.

The performance, in the second half of the concert, started unpromisingly with an announcement that bass Jason Howard was suffering from laryngitis, but had decided to brave the performance. In the end, this added only a frisson of danger; the ghost of 1971 did not return, the soloists all acquitting themselves well, even though tenor Andrew Rees occasionally struggled with some of the more vertiginously tricky passages. The BBCNOW Chorus coped magnificently with the irregular meters, sudden shifts in harmony and awkward intervals (‘the augmented this and and diminished that’ as Chorus Director Adrian Partington memorably said before the performance), the children’s chorus of Ysgol Gerdd Ceredigion provided a clear and confident contrast to the rich adult voices. BBCNOW were as reliable as ever and Rowan Williams added his inimical gravitas to the readings. One might nitpick here and there – for example I would sometimes have liked a bit more clarity in the choral singing; textures became a little muddy at times – but, it is fair to say that this time the Missa was given a performance that would not stand in the way of critical assessment of the work itself. So what of it?

I think, on balance, the expectations were completely justified. The opening phrase of the Kyrie, with its scotch snap rhythms and interjections from trumpet take you unmistakably into the sound world of the composer. It is an evocative beginning – the darkly incantatory mood befitting the text. The Kyrie, imparted three times by the choir and separated by two Christe sections for soloists, builds threateningly without being allowed to reached a climax. The Gloria is conventionally sectionalised. On first hearing my reaction was that the writing was superb, but the ideas were not interesting enough to be really compelling, a view that changed on a second listening. There is a exhilaratingly frenzied Gloria, a lyrical Laudamus Te for soloists, a metrically tricky – and very catchy – Domine Deus, a lamenting Qui Tollis with agonised woodwind lines. The brief Quoniam then provides a bridge to the Cum Sancto Spiritu, which appears to liberate the rhythms of the Domine Deus.

It is in the Credo that Williams provides her coup de théâtre. Former Director of BBCNOW Huw Tregelles Williams described before the performance that to Williams, an agnostic, the Credo was as much to do with mysticism as with the challenge of belief. After a hushed Et Incarnatus Est – a perfectly judged moment of transition – the children’s voices are introduced. The effect is astonishingly moving, even more so for being reserved for this point. The mass text then continues for moment, followed by a reminiscence of the carol material. This leads to The Beatitudes, read in Welsh with a simple instrumental accompaniment. The effect seems to emanate somewhere from the mystical past, as if we are witnessing some ancient druidic ceremony. As a Welshman abroad it made me profoundly homesick.

The following movements follow a more conventional pattern. The Sanctus arrives in a blaze of glory with the return of the scotch snap rhythms and other material from the opening Kyrie. Chorus, soloists and orchestra are set against the incantatory sounds of the children’s voices. This leads to two radiant Osannas before a reaching an ethereal close. There follows a Benedictus for choir and soloists. It is a simple and dignified movement with beautiful solo lines for woodwind. It leads directly to the more anguished Agnus Dei, the material for which again recalls the opening of the work, and a bleak Dona Nobis.

Rian Evans, in her generally positive review of the performance, did, nevertheless, called the work ‘strangely repetitive.’ I can, to a point, see what she means – my initial criticism of the piece was the extent to which the music from the opening Kyrie reappears throughout. Perhaps we have both missed the point, however. The reuse of this material is not simply repetitive, it is symphonic; it never reappears in exactly the same way. In this sense the work is a tour de force of integration and development. BBCNOW, supported by the efforts of a number of people, took quite a risk resurrecting this work. It was a triumph. One can only hope that there will be a commercial recording very soon.

The first half of this all-Williams concert also consisted of fine performances of her perennially popular Fantasia on Welsh Nursery Tunes and Trumpet Concerto played by Huw Morgan. The former is performed very often in Wales. It might be described as a ‘medley’, though that does an injustice to the cleverness with which she weaves the succession of melodies together. And its infectiously rumbustious outer sections frame, at the presentation of the melody Si hei lwli mabi, a lyrical core. The Concerto, written for Williams’ favourite instrument, is a very fine work indeed, to my mind superior to more oft-heard pieces by the likes of Arutunian and Böhme. Despite the traditional three movement pattern, the opening movement is more lyrical than energetic. As in the Missa Cambrensis it features scotch snap rhythms, as well as fanfare figures on the trumpet and an almost Mediterranean lushness to the orchestration. The central movement is a passacaglia on a 12-note idea, though the language is not serial. Elements from the first movement intrude as the funereal theme builds with powerful inevitability and impressive control. The final movement seems to reinterpret the mournful atmosphere as diabolic dance. It is marvellously exhilarating, catchy but also a little disturbing.

When I was at the WMIC all those years ago I picked up a trumpet and piano version of the Williams Trumpet Concerto. It was written in the composer’s hand, there being no engraved copy. This situation, I am happy to report, will soon be rectified with the release of a new edition by Tŷ Cerdd. The work is difficult, but definitely accessible to talented amateur players. If you are a trumpet player looking for repertoire, look no further.

You can hear this concert on BBC iPlayer for the rest of March, here.

0 comments

The Bangor Music Festival (1st–6th March) begins with a St. David’s Day choral extravaganza performed by Côr Glanaethwy. The programme includes music by a number of living composers, including Karl Jenkins, Gareth Glyn, Einion Dafydd and Eric Whitacre. The vocal theme continues on 3rd with a concert by soprano Elin Manahan Thomas and on 5th with the Swingle Singers performing a selection of newly-commissioned works. On 2nd there is a concert of experimental music and theatre performed by the Bangor New Music Ensemble and The Fusion Ensemble; on 4th a programme of music by Welsh women composers; and the final day features talks, papers and a piano and electronics concert with Xenia Pestova and Electroacoustic Wales.

The London Ear Festival makes little effort to provide a narrative to its five-day festival (9th–13th), but that hardly matters given the range of interesting events on offer. There are several workshops: one each on contemporary harp, violin and percussion techniques and one in which composers are invited to bring their scores for a discussion session with Artistic Directors Gwyn Pritchard and Andrea Cavallari. The daily concerts include around thirty UK and world premieres, some of which will be first performances of works by finalists from the London Ear Festival Composers’ Competition.

In Birmingham, the Frontiers Music Festival (4th–18th) describes itself as ‘a two week frenzy of ground-breaking, window-shattering and earth-shaking new music.’ Try not to be put off by the website, which looks and navigates like a work-in-progress; what it describes sounds enticing, including works by Gavin Bryars and Errollyn Wallen and ensembles such as the Hans Koller Quartet and the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. There will also be a focus on emerging composers Christine Cornwell, Kirsty Devaney, Anna Palmer and Emily Wright.

A nationwide event to look out for this month is CoMA’s Open Score Project. Over the last ten years it has commissioned composers to write aesthetically honest but technically accessible works for flexible ensembles. Focused largely around 4th–6th March (though there is also an event in Manchester on 27th Feb) there will be performances, workshops and a conference to promote this repertoire. The events are nationwide, so there is plenty of opportunity to get involved.

There are two major opera revivals in March. Philip Glass’s Akhnaten is the last of a trio of operas that explore the themes of science, politics and, in this case, religion. The libretto, written in Egyptian, Hebrew and Akkadian, explores the banishing of many gods in favour of one ‘sun’ god. It hasn’t been mounted in London for 30 years, The Guardian describing it as 'A once-in-a-generation chance to hear Glass’s score in the theatrical flesh.’ The plot to Gerald Barry's The Importance of Being Earnest needs no introduction. I’ve recommended it on this blog before; it is a wonderfully inventive score that won the 2013 Royal Philharmonic Society Award for best large-scale composition. The Royal Opera House production (29th–3rd April) is highly recommended.

Other world premieres to look forward to this month include, in France, on 5th: Raphaël Cendo's Radium at IRCAM in Paris (this concert also includes the French premiere of An Experiment With Time by Daniele Ghisi); works by Manfred Trojahn and Matthias Pintscher played by Ensemble Intercontemporain at the Philharmonie de Paris on 23rd; and another work by Pintscher, Three pieces for cello and piano, as part of a concert on 31st at the Aix en Provence Easter Festival that will also feature works by Pierre Boulez. UK premieres include: on 12th at the CBSO Centre, Hans Koller’s Twelve Re-inventions for George Russell, the composer being on hand for a pre-concert talk; on 13th at LSO St. Luke’s, Darren Bloom’s Dr Glaser's Experiment; Elizabeth Ogonek’s Sleep & Unremembrance at the Barbican on the same day; and a new work for soprano, piano, flute and cello by Judith Weir at Wigmore Hall on 29th. Regional premieres include, in Scotland, James Macmillan’s Little Scottish Mass at Usher Hall on 18th, and, in London, Penderecki’s La Follia for solo violin (21st), Poppe’s Speicher (10th) and John William’s Soundings (22nd).

0 comments

The shenanigans at English National Opera would seem to be an obvious vindication of Micawber's advice regarding fiscal contentedness. We are entitled to ask, however: to what extent should an arts organisation be ruled by the dictates of the free market?

In his article yesterday in the Guardian, Darren Henley, Chief Executive of Arts Council England, defended their decision to remove ENO from its portfolio of 686 supported arts organisations, instead moving it to an almost exclusive ‘must try harder’ category of its own. In doing so it cut ENO’s funding from £17,470,853 to £12.38m, whilst also providing a transition grant that amounts to about £5.5m over 15/16–16/17. There is no certainty that the organisation will receive any support at all beyond 2017. The reasons he gave for this action include: that ENO has repeatedly failed to live within its budget, having been bailed-out by ACE on a number of occasions; that it has failed to innovate rapidly enough (outreach work, live streaming etc.); and that its audience levels are low.

The problem of attendance, on the face of it at least, seems clear. In 2010/11 their auditorium was 80% full; in 2011/12, 71%; 2012/13 a miserable 66%; and in 2013/14 it was 75%. Royal Opera House, whose success was trumpeted by Darren Henley, runs consistently above 90%. The question is: to what extent do such numbers matter?

With a capacity of 2359, ENO’s home, the London Coliseum, is always going to be difficult to fill. Would we, for example, be having this argument if ENO’s auditorium was half the size, with the organisation having either a) to turn punters away b) raise prices to keep numbers down c) put on more performances to cope with the demand? If we take two other major arts companies in handsome receipt of ACE funding, the National Theatre and RSC, these companies have capacities of 1150 (main auditorium) and 1040 respectively. Both receive funding at similar levels as ENO used to get: £17,217,000 for the NT: £15.447,000 for RSC. They have attendance figures in excess of 90%, which maybe isn't surprising given the venue sizes. I understand that Royal Opera House achieves its 90%+ figures on a venue size not much smaller than ENO. I suspect there are rather complicated reasons for this, however—historically ROH has had more status, more pulling-power and the ability to attract rich concertgoers that its more proletarian cousin.

In terms of ENO’s apparent failure to innovate, it is certainly true that ROH was, for example, ahead in broadcasting its performances in cinemas. Other regional companies also do excellent and laudable outreach work. I want to see ENO do more of these things too. We have, however, to ask ourselves: what is an opera company for? It is to mount performances of operas, by which I mean live opera. I, personally, am not that interested in watching an opera on a cinema screen and no amount of outreach work is going to make me feel better if the live performance I am attending is execrable. The irony is that, amidst all of this hoopla over the parlous state of ENO’s finances, it is not failing in its artistic mission (see, for example, its lauded performances Peter Grimes in 2014 Mastersingers in 2015 or the recent The Force of Destiny).

That ENO is artistically healthy makes it all the more inexcusable that cutting funding is being presented as a way of making the company more viable. In fact, the cuts are having the opposite effect. There are threats, for example, to cut the pay of the the Chorus by 25%, with many believing that this is the prelude to replacing it with part-timers. As representatives from the Chorus of ROH pointed out yesterday, it is an approach that would lead only to further financial ruin.

The third factor being used to justify cutting ENO’s funding is that it has consistently failed to live within its budget. A recent estimate puts the figure of ACE bailouts at £33m over the last 20 years. Let’s think about this for a moment. A company that is mounting one of the most expensive art forms, isn’t doing such a bad job with audience attendance and is receiving rave reviews is running over budget by an average of £1.65m per year. Let’s – just for once – also give management the benefit of the doubt; after all the brightest minds have been trying to bring down the cost of running ENO for years. Could it be that they have failed because the Arts Council have, in fact, underestimated the cost of producing live opera at the Coliseum?

My profound hope is that all is not what it seems in this Arts Council funding farce. Perhaps the real aim is to frighten ENO a little so that they make some savings and then welcome them back into the portfolio fold with a realistic level of funding. Whilst this opera buffa plays out, however, let’s pray that it doesn’t result in the destruction of one of our finest opera companies.

0 comments

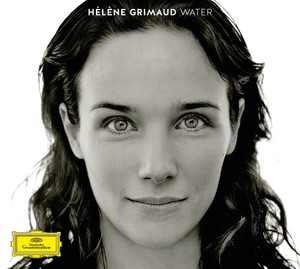

I don’t often like themed collections of music, especially where they emphasise those qualities – 50 relaxing classics! The Only Classical Chillout Album You'll Ever Need! – that seem to require that music should send the listener to sleep. Despite this, I like Hélène Grimaud’s new disk ‘Water’ on DG a lot. There’s quite a mixture of piano music on it, including works by Berio, Fauré and Takemitsu. The works are all more or less inspired by the theme of water. What makes the sequence work exceptionally well, however, are the imaginative transitions by Nitin Sawhney. These separate each work, adding a feeling of coherence to the whole whilst being interesting in their own right. I don’t often like themed collections of music, especially where they emphasise those qualities – 50 relaxing classics! The Only Classical Chillout Album You'll Ever Need! – that seem to require that music should send the listener to sleep. Despite this, I like Hélène Grimaud’s new disk ‘Water’ on DG a lot. There’s quite a mixture of piano music on it, including works by Berio, Fauré and Takemitsu. The works are all more or less inspired by the theme of water. What makes the sequence work exceptionally well, however, are the imaginative transitions by Nitin Sawhney. These separate each work, adding a feeling of coherence to the whole whilst being interesting in their own right.

A noted Gorecki specialist pointed out recently that Nonesuch were largely responsible for popularising the composer’s works outside his native Poland. And now it has released a 7-CD retrospective of his music, including recordings of his Symphonies No. 3 and 4, String Quartets, Miserere, Lerchenmusik and …songs are sung. A less well-known Polish composer, Marian Sawa is represented on Naxos by the release of a disc of violin works, some of which were not discovered until after his death in 2012. Also new on the label this month are a programme of flute works by John Cage; works for winds by Jan Van der Roost; and dance-inspired works by Puerto Rican composer Roberto Sierra.

On NMC Ryan Wigglesworth conducts a programme of his own music that includes his dramatic cantata Echo and Narcissus. Also currently available for pre-order (you can hear musical extracts if you follow my links) are James Wood’s new disk Cloud-Polyphonies and Edward Cowie’s In Flight Music, which consists of his String Quartets 3–5.

On Wergo are works by Dimitri Terzakis which are, in various ways, inspired by literature and Pēteris Vasks’ String Quartets 2 and 5 played by Spīķeru String Quartet. The label has also released a portrait DVD of composer and theologian Dieter Schebel.

On Hyperion is Alec Hoth’s A Time to Dance, a cantata that celebrates times and seasons. Also included is a set of evening canticles and a new setting of George Herbert’s Praise to the God of Love. On Divine Art, finally, is Lunaris, a collection of works for piano and chamber ensemble by Swedish composer Jonathan Östlund.

0 comments

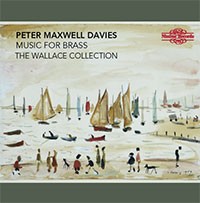

From his exuberant Opus 1, the Sonata for Solo Trumpet written for Elgar Howarth, music for brass has been an important part of the Maxwell Davies catalogue. This disk provides a useful summary of his wide-ranging contribution to the medium.

The programme is made up of three attractive and accessible works, The Pole Star March (1981), Tallis, Four Voluntaries and Fanfare for Lowry (2000) and three that present difficult technical and aesthetic challenges: Litany for a Ruined Chapel between Sheep and Shore (1999) for solo trumpet, Sea Eagle (1982) for solo horn and his Brass Quintet (1981). The mixture of pieces provides a balanced and entertaining programme, even if I would have been tempted to separate the two works for solo instruments, which some listeners might find tiring presented one after another.

The works scored for quintet feature at the beginning, end and the middle of the programme. The Pole Star March is a short work written in Maxwell Davies’s more relaxed quasi-tonal style. It is attractively melodic, though with an air of melancholy and menace that makes the major chord with which it ends something of surprise. One could easily be forgiven for thinking that the central Tallis, Four Voluntaries were not by a twentieth century composer, since they are written as a pastiche of renaissance counterpoint. They are, nevertheless, ravishing. The three movement Brass Quintet, on the other hand, is an entirely different beast. In its densely argued 35-minute span, Davies pulls no punches, his explicit aim being to create a work of a similar level of aesthetic seriousness as a string quartet. In this he succeeds magnificently. It is a gripping piece, the classically derived forms teeming with brooding energy and inventiveness.

The remaining three pieces are for smaller forces. Fanfare for Lowry, is a little work named after the Heritage Arts Centre in Salford near where Maxwell Davies was born. For much of its elegantly tuneful span it shares the a similar sound world as the Tallis, Four Voluntaries, though there is a more pungent section towards the end. The two works for solo instruments again bring us to the technical extremes of Davies’s style, not to mention those of the instruments for which they are written. The title Litany for a Ruined Chapel between Sheep refers to a building near Davies’s home on the Holms of Ire, Sanday. In it he envisages the trumpet ‘being played in the ruin, open to the skies, in the vast stillness of that haunted land and seascape.’ It is easy, indeed, to imagine this atmospheric piece in situ – it contrasts anguished expressivity with orgiastic passagework, seeming to suggest an ab antiquo religious rite. Sea Eagle, is named after a bird that was reintroduced to Britain having been hunted to extinction. Again there is more than a little of the pictorial about it, the horn swooping and soaring over an extravagantly wide tessitura.

Anyone who has even a fleeting experience of playing a brass instrument will understand that the performances on this disk are astonishing in their virtuosity. This is not to say that they are flawless, but I wonder if that would even be possible given the fearsome technical demands made upon the players. The Wallace Collective have a long association with Peter Maxwell Davies (he was, indeed, present at the recording) and their consummate musicianship is everywhere apparent. As advocates of this repertoire it makes them hard to beat.

0 comments

Christian Morris talks to Michael Sluman, an up-and-coming oboist looking for new works for the bass oboe, an 'extinct' instrument he is trying to revive.

|

|

Michael Sluman |

Tell us a bit about your background. How did you come to play the oboe?

I was very fortunate when I started secondary school to be offered free instrumental lessons. My form tutor was the Head of Music and she really pushed music education, as you can imagine. At the age of 11 I started to have clarinet lessons and within a year I was put in for my grade 3 ABRSM. At this point I really enjoyed music; my school had lunchtime and after-school clubs and there was also a Saturday music school run by the county music service offering a variety of ensembles.

Something I would like to point out is the importance this had on my life. Being from an underprivileged background in state education attending a school which was eventually shut down by Ofsted, having the opportunity to have instrumental lessons for free made me who I am today, and opened my world up to music.

At the age of 13 I started to learn the saxophone alongside the clarinet, but for me I was still quite unsatisfied. I felt I was missing something. When my school closed at the end of year 9 we merged with the school next to us and our school band gained some extra players. This was when I first heard the oboe. I was truly transfixed and I knew that was what I wanted to learn. However, my tutor told me to concentrate on single reed instruments: “Be a master of one and not a jack of all trades.” I took this advice and stuck to single reed instruments, but I was always still dissatisfied. It wasn’t until the end of my GCSEs that I managed to acquire an instrument.

At this point I was playing with my county orchestra, Saturday morning music school, county police band, a community orchestra and school ensembles. Music had seemed to take over my life and I loved every second of it. The thing all of these ensembles had in common, however, was the lack of an oboist. I took the instrument to each of them when I could make a sound. I had a very basic technique but from there I just progressed rapidly.

>> Click here to read the rest of the interview

0 comments

A very happy birthday to Henri Dutilleux, that other great post-war French composer, who would have been 100 on Friday. If you are in Paris for his anniversaire there will be a discussion day at the Philharmonie de Paris, beginning at 9am on 22nd (French required). Afterwards, at 20:30, there is a concert that includes his string quartet Ainsi la nuit. In the UK there is a tribute concert to the composer on 27th January by BBC National Orchestra of Wales at Hoddinott Hall. It also examines the music of composers he inspired. In London on 11th February the Royal College of Music will also host a Dutilleux day, with pre-concert contributions from Kenneth Hesketh, Caroline Potter, Caroline Rae and Mark Hutchinson. Works performed include his Piano Sonata, Les Citations, and the magnificent Symphony No.2, Le Double.

There are several other get-to-know-the-composer events this coming month. As well as the first UK performance of Andreissen’s La Commedia on 12th, there will be a Total Immersion Day dedicated to him at the Barbican on 13th. On 21st, at City Halls, Glasgow, the BBC SSO examine the life and works of Anthony Payne, who this year celebrates his 80th birthday. There will be an interview with the composer and performances that include his 1985 Proms piece Spirit’s Harvest. At Hoddinott Hall on 24th, the BBC National Orchestra of Wales present a programme of music by Huw Watkins: Anthem, Speak Seven Seas, Remember, Partita and Double Concerto. The composer will be present to play the piano. In the same venue the following day there is also the opportunity to hear orchestral music by emerging Welsh composers in the BBCNoW Composition:Wales - Open Workshop.

'Frontiers: Expanding Musical Imagination' is the title of this year’s Peninsula Arts Contemporary Music Festival (Plymouth, UK, 26th–28th February). Apart from the final concert, all events are free. These include two installations: Sonification of Dark Matter by Nuria Bonet Filella and Embodied iSound, by Marcelo Gimes. The latter – ‘an immersive sound ride across frontiers of sonic spaces that members of the public will be invited to enjoy and, at the same time, control in real time’ – sounds particularly interesting. The final concert includes works by Linas Baltas, Federico Visi, David Everson and Eduardo Reck Miranda.

There are two new operas this month. Figaro Gets a Divorce by Elena Langer is based on a libretto by David Pountney. It speculates on the events that might have occurred after Mozart’s great opera. WNO performances run from 21st February–April 7th, with tour dates in Bristol, Milton Keynes, Llandudno, Birmingham, Plymouth and Southampton. At Glyndebourne, meanwhile, Nothing by CT’s very own David Bruce, runs from 25th–27th (with a schools’ performance on 24th). In it the Glyndebourne Youth Opera team join forces with professional singers in a dark tale that examines the meaning of life, ‘lost childhood, the getting wisdom, and the madness of crowds.’

Other world premieres this month include: Serpents of Wisdom for horn and piano by John Casken (London, 1st): Joie éternelle, a new trumpet concerto by Chen Qigang (Amsterdam, 13th); a new work for the London Sinfonietta by Samantha Fernando (London, 11th); Presence for two pianos and percussion by Aurélio Edler-Copes (London, 22nd); an as-yet untitled work by Daníel Bjarnason for flute, viola and harp (London, 24th); and Song Cycle by Hafliði Hallgrímsson (Edinburgh, 27th).

If you are an organ fan, it’s also worth making a trip to the Philharmonie de Paris for the inauguration of the the organ on 6th February. This will include the opportunity to hear Ligeti’s majestic Volumina.

0 comments

.jpg) The death of Pierre Boulez marks the end of a remarkable, and often controversial, era in Western music. The last, and arguably greatest, composer of the postwar avant garde, he was also one of our finest conductors, writers and theorists. The death of Pierre Boulez marks the end of a remarkable, and often controversial, era in Western music. The last, and arguably greatest, composer of the postwar avant garde, he was also one of our finest conductors, writers and theorists.

Viewed with hindsight there seems to be a certain inevitability about Boulez’s rise. The historical direction of music, particularly the development of serialism at the beginning of the century briefly gave the impression that music could be unified under one stylistic banner. Boulez was ideally placed, both in age and temperament, to take advantage of this fact.

Whilst also a gifted pianist, it was his early promise in mathematics and science that provide the first indication of the Boulezian mindset. In it composition was objectified – the composer’s responsibility was not so much self-expression, but the cultivation and development of a received style. It was an approach that could make Boulez searing in his criticism of others. For example, though he benefitted greatly from his participation in Messiaen’s famous harmony classes in the early 40s, he came to reject the music of his teacher, eventually calling his Turangalîla-Symphonie (1946–8) ‘brothel music’. He was also known to have heckled a neo-classical work of Stravinsky during a concert in 1945 and snubbed Henri Dutilleux at the premiere of his First Symphony in 1951.

Boulez’s impatience derived from what he regarded as the historical inevitability of the serial technique, which he had gradually discovered through composer and theorist René Leibowitz. His first compositions (e.g. Notations, 1945) explored the method and, by the turn of the decade, he was pursuing the system to its logical conclusion by applying the series not just to pitch, but to timbre, duration and intensity. It was also around this time that he made some of his most famously intemperate remarks about other composers, berating them for not properly exploring their musical inheritance (Schoenberg est mort, 1952), and labelling those who did not feel the necessity of serialism as ‘useless’ (Eventuellement…, 1952). His polemical nature meant that the air of controversy never entirely left him. This was most farcically manifested following the New York attacks in 2001, when he was briefly detained as a terrorist suspect in Basel, having once remarked that it might be a good idea to burn down all the world’s opera houses.

The sometimes divisive nature of Boulez’s utterances, together with the early direction of his music, imply a dogmatic nature, an insistence that his way was the only way. Elements of this are certainly true, but his development was, in fact, anything but dogmatic. He seems quickly to have realised that his experiments with total serialism, whilst necessary, were a dangerous cul-de-sac. Subsequent works, beginning with Le marteau sans maître (1953–5) showed a loosening of approach to the serial method and even the granting of freedom to performers, especially in allowing them to choose a route through a work (e.g. Third Sonata, 1955–7; Pli selon pli, 1960–2, rev. 1989–90; or Domaines, 1961–8).

From the 1960s Boulez was increasingly distracted by a second but equally brilliant career as a conductor. This, by his own admission, he came to almost by accident. When he founded the Domaines Musicale concerts in 1953 to promote new music there were few who were qualified to conduct the repertoire. It often, therefore, fell to Boulez to direct. He soon began to be in demand in this new role, eventually quitting France in 1959 to conduct concerts of contemporary repertoire with the Südwestfunk radio station. More posts followed with his appointment as guest conductor with the Cleveland Orchestra in 1967 and principal conductor of the BBCSO and New York Philharmonic in 1971. He returned to France in 1977 to take up the position of director of IRCAM, a role which also led to him founding the Ensemble Intercontemporain, another platform for his conducting, as well as composing, activities. There were also major invitations to conduct operas, including Pelléas et Mélisande in 1969 and 1992 (the latter with WNO winning a major international award); Wagner’s Ring at Bayreuth in 1976; and Janáček’s From the House of the Dead in 2007. Boulez was noted for bringing textural clarity to his performances, often revealing hitherto inaudible detail, and for perfection of execution.

The increased preoccupation with conducting led to a gradual diminution in Boulez’s composing output. The 70s saw the just five new works, the most compelling of which was Notations (1978–), an exhilarating recomposition for large orchestra of his early piano work. The 80s also saw explorations of the technology made possible by IRCAM, with Répons (1980–4) for two pianos, harp, vibraphone, xylophone, cimbalom, ensemble and live electronics; Dialogue de l'ombre double for clarinet and electronics (1985); and a version of …explosante-fixe… (1986) for vibraphone and electronics. There were also many revisions of older works, an activity that was not necessarily a sign of dissatisfaction; for Boulez the serial universe opened up the possibility of endless permutation. It was perfectly natural, therefore, that he should explore old works, sometimes completely recomposing (sur Incises, Notations), sometimes merely revising.

From 1980 onwards he received a number of awards, including: the French National Award of Merit (1980), several honorary doctorates, the Wilhelm Pitz Prize of the City of Bayreuth (2001), the Kyoto Prize (2009), the Giga-Hertz-Award for electronic music (2011), the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement of the Venice Biennale (2012), the Frontiers of Knowledge Award (2013) and honorary citizenship of Baden-Baden (2015). No doubt the realisation that he was now a cultural insider helped to mellow him a great deal in his later years. This was apparent in two of his recent interviews. In the first (2012), with reference to his early works, he acknowledged his need to balance the ‘constructivism’ he encountered (and even found ‘a burden’) in the works of the Second Viennese School with a freer approach. In another (2009) he talked about how music cannot be compared with science, in that in science things progress, whereas the music of a particular time is not to be considered superior to that of an earlier epoch.

By all accounts, and despite his public persona, Boulez was always a man of great personal charm. Daniel Barenboim, who knew him well, remarked yesterday: ‘Pierre Boulez has achieved an ideal paradox: he felt with his head and thought with his heart. We are privileged to experience this through his music. For this, and so much more, I will always be grateful.’

0 comments

The Shadows of Time, Le temps l’horloge, Mystère de l’instant. Henri Dutillleux was a composer always interested in the concept of time. And, as I write this on a cloudy day in Nice, I can scarcely believe that another year has past. It is especially appropriate to find my mind turning to the composer whose music has much occupied me over the last few years, since 2016 – 22nd January to be precise – marks 100 years since his birth. There are a number of events in 2016 celebrating this important anniversary, including discovery days in February (at Royal College Music) and April (at the Barbican). Elsewhere you will find his name cropping up with much greater regularity in concert programmes. The Shadows of Time, Le temps l’horloge, Mystère de l’instant. Henri Dutillleux was a composer always interested in the concept of time. And, as I write this on a cloudy day in Nice, I can scarcely believe that another year has past. It is especially appropriate to find my mind turning to the composer whose music has much occupied me over the last few years, since 2016 – 22nd January to be precise – marks 100 years since his birth. There are a number of events in 2016 celebrating this important anniversary, including discovery days in February (at Royal College Music) and April (at the Barbican). Elsewhere you will find his name cropping up with much greater regularity in concert programmes.

2016 will also see the 80th birthday of Steve Reich, the 100th birthday of Alberto Ginastera and Milton Babbitt, the 150th of Erik Satie and Ferruccio Busoni. You can also expect to hear more of their music this year. In the meantime, I offer you my picks of 2016. Entirely subjective and not comprehensive, they nevertheless give a snapshot of some of the treats in store for us.

I also wish all readers and especially CT members a happy, peaceful and, above all, musical New Year!

January

9th UK premieres of: Joan Magrané Figuera’s ...secreta desolación…, Salvatore Sciarrino’s Libro notturno delle voci for flute and orchestra and Jay Schwartz’s Delta – Music for Orchestra IV. BBCSSO, City Halls, Glasgow.

8th–9th Pierre Henry Continuo ou vision d'un futur. Philharmonie de Paris, Paris.

10th Boston Symphony Chamber Players – Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Henri Dutilleux’s Birth. New England Conservatory Jordan Hall, Boston.

12th Composers' Workshop: Writing for Voices with Judith Weir and the BBC Singers.

13th Simon Rattle conducts Dutilleux’s L'arbre des songes and Métaboles. LSO, Barbican, London.

14th–16th Magnus Lindberg, Violin Concerto No.2 (US Premiere). NYP, New York, David Geffen Hall.

15th Desmond Clarke Viola Concerto (world premiere). Barbican, London.

16th Francesca Verunelli Secondo Quartetto (world premiere). Quatuor Zaïde, Philharmonie de Paris, Paris.

22nd–23rd OPUS2016 Interactive Open Workshops. Barbican, London.

February

11th Dutilleux Day. The RCM presents a day of events to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Henri Dutilleux.

11th&12th Samantha Fernando New Work in four movements (world premiere). London Sinfonietta, Southwark Playhouse London.

12th Louis Andriessen: La Commedia (UK premiere). BBCSO, Barbican, London.

13th Total Immersion: The Music of Louis Andriessen. A day of events exploring the music of the composer. Barbican, London.

21st Discovering Music 2: Anthony Payne. BBCSSO, City Halls, Glasgow.

24th Composer Portrait: Huw Watkins. BBCNOW, BBC Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff.

24th&25th Michel van der Aa The Book of Disquiet (UK premiere). London Sinfonietta, The Coronet Theatre, London.