|

|

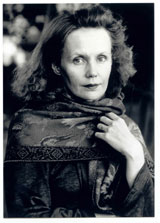

Kaija Saariaho

Gavin Thomas introduces the work of Kaija Saariaho (1954– ).

Overview

The outlandish work of Kaija Saariaho offers a tantalising hint as

to what the classical music of the 21st century might sound like.

More than any other major composer of her generation, Saariaho has

made electronic and computer-generated sounds a constant ingredient in her music,

while the scientific analysis of instrumental sounds and timbres also plays

a major role in her compositional method.

But what’s equally distinctive about her work is its constant

ability to transcend its own laboratory origins, and to create musical worlds

not only of startling strangeness and originality, but also of great luxuriance and beauty.

Although a native of Finland, Saariaho has lived largely Paris since 1982,

where she has been closely associated with IRCAM, the gargantuan

music research centre in the bowels of the Pompidou Centre

established by Pierre Boulez in 1977.

Funded at vast expense by an obliging French government, IRCAM’s

charter was nothing less than to lay the ground for the music of the future,

bringing together musicians and scientists to investigate new ways of making

sound through electronics and novel instrumental techniques.

The results of Saariaho’s researches at the centre can

be heard, most obviously, in her music’s extraordinary soundworld,

with its myriad new ways of bowing, blowing and plucking –

coaxing perplexingly odd sounds from familiar instruments, which are then

further enriched through electronic transformation.

Amers, for cello and ensemble, is a

particularly striking example of Saariaho’s style at

its densest and most exuberant, using a barrage of

unorthodox performing techniques along with a special IRCAM-designed microphone

which allows each of the solo cello’s four strings to be

independently amplified and electronically treated during performance.

It’s not just the sound-surfaces of Saariaho’s works

that are persuasively novel, but also their structure. Many of

her works base themselves formally on natural phenonema and shapes – crystals, spirals, waterlilies,

the Northern Lights, to name just a few of her

avowed inspirations – which are at once aesthetically pleasing and

scientifically complex.

She’s also a composer for whom the spoken

or sung word has been central, not only in her many vocal

works, but also in the many of her “instrumental” works,

in which the performers are often asked to recite fragments of

text or verse whilst playing, most memorably in the string quartet Nymphea,

in which the quartet players’ whispered utterances create

a secondary tangle of poetic fragments which seem to offer

a dream-like commentary on the music itself.

Saariaho’s interest in exploring the minutiae of instrumental effects has

meant, not surprisingly, that the majority of her

pieces are for small-scale instrumental or vocal forces without or – most characteristically –

with electronics.

Many of her works feature flute or cello, two instruments

to which she’s returned repeatedly, as in NoaNoa, for solo flute

and electronics, where the notes of the live flute and the

spoken and sung interjections of the flautist are multiplied in

an electronic hall of musical mirrors, or Près, for solo cello and

electronics, where the voice of the solo instrument

is embedded in a magical penumbra of electronic sound.

In more recent works, Saariaho has turned increasingly towards larger forces and

longer timespans, with a consequent paring-down of musical detail, as

in the violin concerto, Graal théâtre, or her acclaimed recent opera, L’amour de loin,

perhaps her finest achievement to date.

Article and review pages originally published in The Rough Guide

to Classical Music

|