|

|

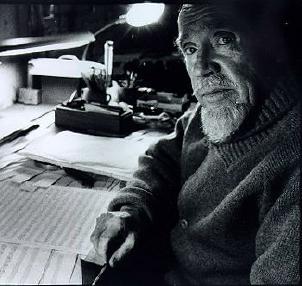

Conlon Nancarrow

Gavin Thomas introduces the work of Conlon Nancarrow (1912–1997).

Overview

For all the modern world’s obsession with technology, Conlon Nancarrow

remains the only classical composer to have established a

lasting reputation on the basis of music written almost entirely for a machine.

Not only does his remarkable sequence of player-piano studies prove

that it’s possible to do without human performers entirely, they also

offer a compelling exploration of the myriad new structures and

sonorities obtainable through mechanical means.

Born in 1912 to a respectable family of Arkansas worthies, Nancarrow spent

a wayward youth learning trumpet, developing a passion for jazz and

determining to become a musician.

In 1934, braving parental displeasure, he trooped off to Boston to study

composition with arch-academics Roger Sessions and Walter Piston,

an experience which seems to have borne little immediate fruit,

although he would later emphasize the value of Sessions’ obsessive contrapuntal training.

In Boston, Nancarrow also joined the Communist Party, and in

1937 went to Spain, fighting for two years in the Civil War

as a foot soldier with the Republican forces.

In

1940, having been denied a passport by a US government suspicious

of his Communist past, Nancarrow decided to leave the increasingly

repressive political climate of the States for Mexico City, where

he lived for the remaining 58 years of his life, acquiring Mexican citizenship in 1956.

The immediate effect of Nancarrow’s move to Mexico

was less than propitious. Already politically ostracized, he now found himself almost entirely

cut off from US musical life and the chance to have

his increasingly challenging music performed.

Making a virtue of necessity, in 1947 Nancarrow acquired a player-piano,

or pianola – a mechanical piano operated by a roll of punched paper –

on which he could “perform” his own music.

The player-piano’s ability to execute any sequence of notes – no matter how

fast or rhythmically complex – also allowed Nancarrow to explore

the arcane rhythmic structures which became the basis of his mature music,

and whose difficulties would have defeated even the best performers of the time.

The following quarter century was one of extreme musical isolation,

as Nancarrow laboured on the immense series of Studies for

Player Piano which form the bulk of his output.

The first step towards recognition was the 1969 Columbia recording

of twelve of the studies, but it wasn’t until 1977, and

the first part-publication of the studies, followed

by further recordings, that Nancarrow’s work began to be widely known.

In 1981, in the wake of his burgeoning reputation, he returned

to the US for the first time since 1947 – though subsequent

enquiries about the possibility of his going back to

live in his home country were stymied by the

bluestocking attitudes of American officialdom.

More positively, Nancarrow also found a new generation of virtuoso

performers rising to the challenge of his music:

Yvar Mikhashoff’s pioneering orchestrations of selected

piano-player studies were brilliantly realized and recorded by

the Ensemble Modern, whilst the wizardry of performers such

as pianist Ursula Oppens and the Arditti String Quartet persuaded Nancarrow

to return to writing for live performers after a gap of some forty years.

Article and review pages originally published in The Rough Guide

to Classical Music

|